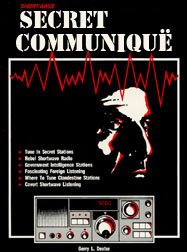

Above: A model shows off one of the outfits at a secret exhibition in the basement of a nondescript Tehran apartment building.

Above: A model shows off one of the outfits at a secret exhibition in the basement of a nondescript Tehran apartment building.Tehran — FIRST, a text message arrived. The brief note invited recipients to call about the location of a secret meeting. A cryptic phone conversation followed. "Who referred you?" a woman asked. "Who do you know?"

A man drove up in a Korean hatchback and dropped off a coded slip of paper. The directions led to a bland apartment building in the north of this capital.

There, men and women draped in coats and head scarves entered the lobby, their faces sullen. A young man examined their documents for signs of forgery before allowing them to pass down the staircase to the basement and into a sea of bare skin and perfume.

Amid air kisses and gossip, techno and hip-hop music thumps. The guests slide out of dark overcoats to unsheathe daringly low-cut dresses and open-slit gowns, form-fitting sweaters and go-go boots, skin-tight T-shirts and acid-washed jeans. Skinny, long-legged models giggle as they slip into outfits of satin and silk. A red carpet serves as a runway.

A clandestine Tehran fashion show glitters gloriously to life.

"Everyone is putting on a show," declares Azita, a 46-year-old designer attending the show with her 20-year-old daughter, giddily taking in the swirl of lights, music, perfume and colored fabrics. "All the ladies have gotten into the fashion business. We love it so much because the clerics hate it." She and others taking part and watching the show asked that their family names not be published for fear of retribution.

Since the beginning of the Islamic Republic 28 years ago, those who opposed Iran's Islamic system have carved out sanctuaries from its restrictions. Those islands have become more and more elaborate. They include outlandish liquor- and drug-soaked parties, art exhibitions, showings of banned movies, hip-hop concerts.

Fashion shows of outfits that abide by Islamic dress codes are common. All-women shows of new designs that don't are relatively rare. But fashion exhibitions featuring scantily clad models parading before mixed audiences of men and women almost never take place here. At least one major Internet service provider even forbids Google searches for the word "fashion."

None of that deterred Sadaf, the 30-year-old designer behind this showcase. For dozens of days and sleepless nights, she planned and organized. She scoured the bazaars for exotic fabrics. She scribbled designs onto scraps of paper in a spare room of her parents' flat in north Tehran, then hired a tailor to turn her concepts into clothing. She took the risky step of asking a friend to put up a website,

http://www.sadaft.com/ .

She signed six models, four of them from abroad, footing the bill for their airfare to Tehran. She could have used local models, she said, but their figures weren't up to "international standards."She and her boyfriend combed the city and worked contacts for weeks in search of a venue that would agree to lend them a space for such a controversial event. Five days before the show, a friend of a friend agreed to rent them this basement for $1,000. They signed a document promising that all women would abide by Islamic dress codes.

"I'm a little terrified to do this," says Sami, a professional model. She spent six years posing for shoots and working catwalks in the United Arab Emirates city of Dubai across the Persian Gulf before moving back to Iran last year.

Working as a model in Tehran meant going underground.

"We talk about modeling on the phone," Sami says. "But we don't talk about parties and shows on the phone. The designers call us when they need us. People are invited at the last minute. No one knows the address. Everything is like that here in Iran. Everything is private. No one works publicly."

Sadaf's outfits range in price from $130 to $760, a fortune in a country where schoolteachers earn about $2,500 a year. She sells four outfits this night, enough to cover the rent.

Some of the musicians perform afterward. The models, guests and organizers mingle over tea, refreshments and live music, savoring a night of respite from the Islamic Republic's dour fashions and rules.

Even as government censors attempt to tighten restrictions on movies and music, young Iranians now groove to their own tunes on iPods or Walkmans as they go down the street, a rare sight only five years ago. Women still comply with the requirement of keeping themselves covered, but the coverings have become tighter, more colorful and shorter, their mandatory scarves more flimsy and revealing.

Some worry that the retreat into superficial pleasures portends ill for Iran's future.

"As a backlash against the ideology imposed by the state and a mutiny against what they were indoctrinated in the schools … the youth are becoming more and more hedonistic," said Ali Dehbashi, the publisher of a well-known literary quarterly magazine, Bokhara.

The young appear to be making a conscious decision. They learn how to model watching fashion channels that are only a few clicks of the remote control away from programs by Los Angeles exiles urging them to rise up against their government. They organize shows with the same passion and stealth that dissidents might use to plot against authorities.

They invest their ingenuity into pushing the boundaries of fashion instead of politics.

Fashion shows of outfits that abide by Islamic dress codes are common. All-women shows of new designs that don't are relatively rare. But fashion exhibitions featuring scantily clad models parading before mixed audiences of men and women almost never take place here. At least one major Internet service provider even forbids Google searches for the word "fashion."

Fashion shows of outfits that abide by Islamic dress codes are common. All-women shows of new designs that don't are relatively rare. But fashion exhibitions featuring scantily clad models parading before mixed audiences of men and women almost never take place here. At least one major Internet service provider even forbids Google searches for the word "fashion." Additional Link:

Additional Link: